This post was written by Matthew Davis.

Michael Alpers’ 50-year biomedical research odyssey began in 1961 with a mysterious and horrible neurological affliction that was methodically killing women and children in an obscure tribe in Papua New Guinea. It has culminated with revelatory findings linked to two Nobel prizes and insights that continue to inform research into a wide range of diseases including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, diabetes and cancer.

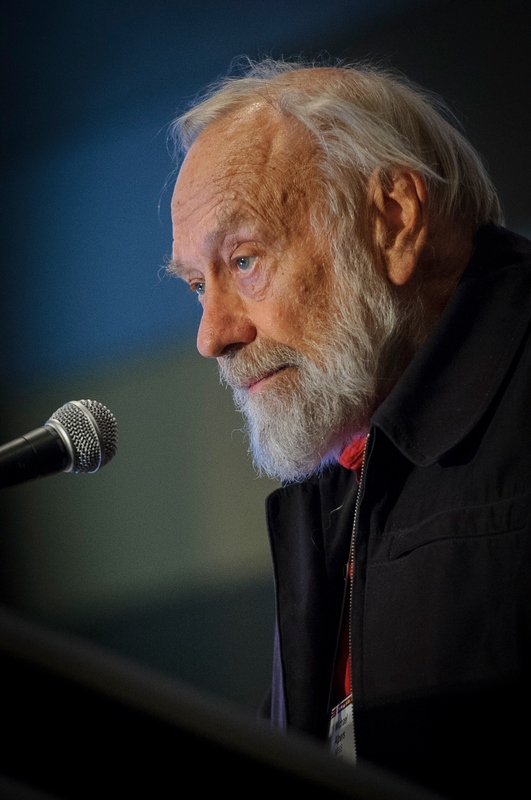

Alpers is the John Curtin Distinguished Professor of International Health at Curtin University in Perth, Western Australia and a member of the Royal Society and the Australian Academy of Science. He delivered this year’s Charles Franklin Craig lecture at ASTMH’s annual meeting, recounting his work with members of the Waisa community in Papua New Guinea and their experience with a brain disease called kuru.

The affliction would begin with relatively mild motor deficits. But over a 12-month period it would steadily progress to total incapacitation and, inevitably and always, death. Particularly puzzling for Alpers was the fact that it occurred almost exclusively in women and children. Alpers efforts to understand the origins of kuru led him to collaborations with Carleton Gajdusek and Stanley Prusiner, whose research, inspired by their work with kuru, helped them win Nobel prizes.

The affliction would begin with relatively mild motor deficits. But over a 12-month period it would steadily progress to total incapacitation and, inevitably and always, death. Particularly puzzling for Alpers was the fact that it occurred almost exclusively in women and children. Alpers efforts to understand the origins of kuru led him to collaborations with Carleton Gajdusek and Stanley Prusiner, whose research, inspired by their work with kuru, helped them win Nobel prizes.

Ultimately Alpers and his colleagues realized kuru bore striking similarities to an infectious disease in sheep called scrapie. They eventually discovered kuru was an infection of the brain. It was spread by a funeral practice of the Waisa community that Alpers called “transumption” in which women and children would cook and consume the remains of the dead.

The work on kuru generated the discovery of what Prusiner called prions, misfolded proteins that lead to brain damage. In kuru and in diseases like Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (mad cow), prions are infectious. Alpers noted that scientists are now also considering that replicating, non-infectious prion proteins are involved in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. In addition, he said scientists are considering their potential role in cancer and diabetes and in fundamental processes like memory and circadian rhythms.

“In the world of prions, there is so much we don’t understand,” he said.

Alpers work with the kuru offered a host of instructive lessons for tropical medicine researchers. For example:

There is enormous value in field research that enlists the disease-affected community as collaborators. Alpers’ repeated trips into the highlands of Papua New Guinea established a tight bond with the Waisa community. He was allowed to conduct autopsies on kuru victims immediately after they died. “All my work was in the community,” he said. “I never saw patients in the hospital.” Alpers performed all of his autopsies “in the village with assistance of relatives.”

Big discoveries require bold leaps and a willingness to take risks. Alpers believes scientists have to be daring to solve major biological mysteries and that any scientist who is “never wrong is not being very bold or creative” He noted that when Prusiner first proposed the idea of the prion as a key to diseases like kuru, “he was given very much abuse at meetings. People would stand up and abuse him openly for his views. But eventually he isolated the gene for the prion and convinced the world that this is a new paradigm in infectious diseases.”

Biological processes operate on their own time and understanding the secrets of an infectious disease can require considerable patience. To test whether kuru was caused by an infectious agent, Alpers and his colleagues at the US National Institutes of Health inoculated two chimpanzees, Daisy and Georgette, with sterile brain matter taken from kuru victims. “After two years they started coming down with behavioral changes,” he said, and eventually, “Daisy began performing quite like a kuru patient. It was uncanny.”

Image: Michael Alpers delivering his ASTMH presentation.